Florenz, Pisa, Padua

zu Dantes Zeit

Florenz, Pisa und Padua zu Dantes Zeit

During the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the cities of Pisa and Florence represented two contrasting yet influential forces in Italian politics, culture, and economy, a period that coincided with the life and works of the great poet Dante Alighieri. Dante, born in Florence in 1265, became a central figure of the Italian literary world, and his experiences in these cities shaped much of his literary output, particularly his views on politics, society, and morality. Pisa, at that time, was a thriving maritime republic known for its significant role in trade and naval prowess in the Mediterranean. The city’s wealth was derived from its strategic location, which facilitated commerce with other Mediterranean cities and regions. Its culture was marked by impressive Gothic architecture, epitomized by the renowned Leaning Tower of Pisa and the grandeur of its cathedral complex. Pisa’s influence extended beyond trade; it was also a center for learning, notably home to one of the earliest universities in Italy, where many of the intellectual currents of the time flourished. This spirit of inquiry and the city’s rich cultural heritage provided a vivid backdrop to the events of Dante’s life, even as he would later come to criticize the moral decay he perceived in the societies around him. In stark contrast, Florence—Dante’s birthplace—was emerging as a political powerhouse during this same era. By the late 13th century, Florence had established itself as a key banking and financial hub. The city’s economy was thriving, supported by a complex system of guilds that governed trade and crafts. The rivalries between these guilds, along with the broader political struggles between the Guelphs and Ghibellines (the factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively), created a tumultuous political landscape. Dante himself was a Guelph, but his views on politics evolved throughout his life, leading to his eventual exile from Florence in 1302 due to factional infighting. Florence was renowned for its cultural achievements and had begun laying the groundwork for the Renaissance, embracing art and literature that celebrated human potential. This environment was rich with intellectualism, as seen in the works of contemporaries such as Giotto in painting and the poetic traditions emanating from the Tuscan dialect, a style that would later influence Dante’s own writing. The city became a crucible for ideas, fostering a spirit of innovation and humanism that would later resonate deeply through Dante’s writing in works such as “The Divine Comedy.” Dante’s experiences in both Pisa and Florence informed his poetic reflections both directly and indirectly. His criticisms of corruption, hypocrisy, and moral failing in political leaders echo the realities he witnessed in these cities. In “The Divine Comedy,” he explores themes of justice and redemption, placing various historical and contemporary figures—inclusive of those from both Pisa and Florence—within his allegorical framework of the afterlife. Dante uses his experiences to critique the socio-political issues of his time, envisioning a world where virtue is rewarded and vice is punished. Moreover, his personal journeys related to exile, the loss of political power, and the upheaval within these city-states are poignantly reflected in his narrative style. In his allegorical journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, Dante confronts the very societal issues that plagued Florence and Pisa, making them emblematic of the larger human condition. Ultimately, the historical contexts of Pisa and Florence during Dante’s time are not only significant in understanding his life and works but also representative of the broader socio-political and cultural transformations taking place in Italy. These cities, with their unique identities and dynamic conflicts, serve as crucial backdrops that shaped a literary master whose themes still resonate today. Through Dante’s lens, the complex interplay of power, spirituality, and morality continues to inspire exploration long after his time.

Was hat Dante Alighieri in Padua gemacht und warum ging er nach Ravenna

Dante Alighieri, einer der bedeutendsten Dichter der italienischen Literatur, hat eine interessante und bewegte Geschichte in seiner Zeit in Padua und Ravenna. Nach dem schmerzhaften Exil aus seiner Heimatstadt Florenz im Jahr 1302 fand Dante zeitweilig Zuflucht in verschiedenen norditalienischen Städten, darunter Padua. In dieser Stadt lebte er etwa 1306 bis 1309. In Padua war Dante vor allem damit beschäftigt, seine literarischen Werke zu vervollständigen und Kontakte mit anderen Gelehrten und Intellektuellen zu pflegen. Die Stadt war ein Zentrum der Wissenschaft und ein Ort, der zahlreiche Philosophen und Künstler anzog. Hier hatte Dante die Möglichkeit, sich mit den Lehren von Aristoteles und den Scholastikern auseinanderzusetzen, was sein Denken und sein Schreiben stark beeinflusste. Diese Zeit erwies sich als fruchtbar, da viele seiner späteren Gedanken und Themen der 'Göttlichen Komödie' in diesen Jahren Gestalt annahmen. Dante war zu diesem Zeitpunkt nicht nur auf seine literarischen Tätigkeiten beschränkt; er engagierte sich auch politisch. Seine Erfahrung im Exil, die seine Perspektiven und Interessen prägten, führte ihn dazu, sich in verschiedenen Republiken und mit unterschiedlichen politischen Strömungen zu befassen. In Padua fand er eine gewisse politische Stabilität und konnte seine Gedanken zur politischen und moralischen Ordnung weiterentwickeln. Nach einer gewissen Zeit in Padua entschloss sich Dante, nach Ravenna zu ziehen, was mit mehreren Faktoren zusammenhängt. Einer der entscheidenden Gründe war die Einladung des Herrschers von Ravenna, Guido Novello da Polenta, der Dante als wichtigen Gelehrten und Dichter schätzte und ihm eine sichere Anstellung anbot. Diese Einladung bot Dante nicht nur einen Ausweg aus den Unsicherheiten in anderen Städten, sondern auch die Möglichkeit, an einem Ort zu leben, der ihm kreative Freiheit und eine unterstützende Umgebung bot, um seine Werke weiterzuentwickeln. In Ravenna lebte Dante von 1318 bis zu seinem Tod im Jahr 1321. Diese Zeit gilt als die produktivste Phase seines Lebens, in der er seine größten Werke, insbesondere die 'Göttliche Komödie', vollendete. Ravenna bot Dante sowohl politische Sicherheit als auch eine interessante kulturelle Umgebung. Hier konnte er neue Ideen aufgreifen, seine Gedanken zu Spiritualität und Philosophie erforschen und eine tiefere Reflexion über das menschliche Leben und die Beziehung zur göttlichen Ordnung anstellen. Zusammenfassend lässt sich sagen, dass Dantes Zeit in Padua und seine Entscheidung, nach Ravenna zu ziehen, von dem Bedürfnis nach Sicherheit, intellektueller Anregung und der Möglichkeit, sich literarisch auszudrücken, geprägt waren. Beide Städte spielten eine wichtige Rolle in seiner Entwicklung als Dichter und Denker und trugen dazu bei, sein Erbe für die Nachwelt zu festigen.

Dante Alighieri, uno dei più grandi poeti italiani, ha avuto un'importante relazione con la città di Padova durante il suo esilio. Dopo essere stato esiliato da Firenze nel 1302 a causa di conflitti politici, Dante si trovò costretto a cercare rifugio in diverse città italiane. Tra queste, Padova rappresentò un luogo di transizione significativo nel suo cammino. Durante la sua permanenza a Padova, Dante si dedicò alla scrittura e al pensiero filosofico. Qui, ebbe la possibilità di interagire con diverse figure intellettuali e politici dell'epoca, ampliando così la sua rete di contatti. Sebbene non vi sia una documentazione dettagliata sulle sue attività specifiche in città, è noto che Padova era un importante centro culturale e accademico, il che avrebbe sicuramente influenzato la sua opera. Dante scrisse alcune delle sue opere in questo periodo, e è probabile che le discussioni con i contemporanei e la vivace vita intellettuale di Padova abbiano alimentato la sua creatività. Tuttavia, il desiderio di ritorno nella sua amata Firenze, e le difficoltà politiche che imperversavano in città, lo spinsero a muoversi ulteriormente verso Ravenna. La scelta di Ravenna come meta finale fu dettata da varie ragioni. In primo luogo, Ravenna era governata da un’umanista patrocinante, Guido Novello da Polenta, che offrì a Dante ospitalità e protezione. Questo era particolarmente importante per il poeta, poiché cercava sicurezza dopo anni di esilio e conflitti. Ravenna rappresentava anche un ambiente più tranquillo e ispirante, il che portò Dante a completare opere fondamentali come la "Commedia", che avrebbe cambiato per sempre la letteratura mondiale. Nell’affetto e nell’accoglienza dei ravennati, Dante trovò una sorta di rifugio e la pace necessaria per dedicarsi alla scrittura. In definitiva, la sua esistenza a Padova fu segnata dall’impegno intellettuale e dalle difficoltà politiche, mentre il suo arrivo a Ravenna si rivelò determinante per la sua produzione artistica e per il ripristino di una certa stabilità nella sua vita. La sua scelta di stabilirsi a Ravenna si dimostrò profetica, poiché fu proprio in questa città che Dante scrisse le parti finali della sua "Divina Commedia", culminando nel suo straordinario viaggio attraverso l'Inferno, il Purgatorio e il Paradiso. In sintesi, il passaggio di Dante da Padova a Ravenna riflette la sua continua ricerca di un luogo dove potesse essere libero di esprimere le sue idee e la sua arte, affrontando le sfide della vita con la determinazione che lo ha reso immortale nella storia della letteratura.

Dante Alighieri, l'un des plus grands poètes de la littérature italienne, a passé une période significative de sa vie à Padoue. Après son exil de Florence en 1302, Dante a erré à travers plusieurs villes italiennes, dont Vérone et Ravenne. Son passage à Padoue, bien que moins documenté que d'autres phases de sa vie, a été crucial dans son développement intellectuel et spirituel. À Padoue, Dante a trouvé refuge et a pu échanger des idées avec d'autres intellectuels de l'époque. C'était un centre culturel vibrant, où il a probablement rencontré des érudits et des poètes. Ces interactions ont sans aucun doute influencé ses réflexions et ses écrits, notamment ceux qui allaient plus tard se retrouver dans sa Divine Comédie. Cependant, la présence de Dante à Padoue n'était pas destinée à durer. La ville elle-même était en proie à des luttes internes et à des conflits politiques. Pour échapper à ces tensions et rechercher une stabilité, Dante a finalement décidé de se rendre à Ravenne. Ravenne offrait un climat plus serein et des possibilités de soutien, tant sur le plan personnel que professionnel. En arrivant à Ravenne, Dante a été accueilli par le seigneur local, Guido Novello da Polenta, qui lui a offert la protection et le soutien nécessaires. C'est au cours de son séjour à Ravenne qu'il a accompli certains de ses travaux les plus renommés, notamment la finalisation de la Divine Comédie, qui est devenue un pilier de la littérature mondiale. En conclusion, le séjour de Dante à Padoue a joué un rôle significatif dans sa vie d'exilé, lui permettant de s'enrichir intellectuellement avant de trouver à Ravenne un havre de paix propice à son génie créateur.

Christoforo Landino - die Kommentare zur Divina Commedia und ihre Illustrationen

Christoforo Landino (1440-1510) war ein italienischer Humanist und Gelehrter, der vor allem für seine Kommentare zur "Divina Commedia" von Dante Alighieri bekannt ist. Landino wurde in Florenz geboren und war eine zentrale Figur der literarischen und kulturellen Bewegung des Renaissance-Humanismus. Er studierte an der Universität in Florenz und hatte direkten Kontakt zu bedeutenden zeitgenössischen Denkern, was seine intellektuelle Bildung prägte. Sein bekanntestes Werk sind die Kommentare zur "Divina Commedia", die er erstmals 1490 veröffentlichte. In diesen schriftlichen Erklärungen bietet Landino eine umfassende Analyse der komplexen und oft symbolischen Inhalte von Dantes Meisterwerk. Seine Kommentare sind bemerkenswert für ihre detailreiche Erörterung der philosophischen, theologischen und literarischen Aspekte der Komödie sowie für die historische Kontextualisierung der verschiedenen Figuren und Ereignisse, die Dante beschreibt. Landino hat es verstanden, die tiefschichtige Symbolik Dantes zu erläutern und dem Leser verständlich zu machen, wodurch er zur weiteren Verbreitung und Popularisierung Dantes Werks in der Renaissance beitrug. In seinen Kommentaren stresst Landino vor allem die ethischen und moralischen Lehren, die aus Dantes Reise durch die Hölle, das Läuterungsgefilde und den Himmel zu gewinnen sind. Er diskutiert die Relevanz von Dantes Schriften für seine Zeit und hebt die zeitlose Natur der Themen hervor, die auch für die Menschen seiner eigenen Epoche von Bedeutung waren. Landinos Werk ist nicht nur eine Erklärungsgrundlage, sondern auch eine Interpretation, die Dantes Anliegen in den Kontext der Humanismus-Bewegung stellen wollte. Zudem war Landino auch bekannt für seine eigenen poetischen Werke, die in der Tradition von Dante und Petrarca standen. Er war sowohl Dichter als auch Kritiker und versuchte, die literarischen Standards seiner Zeit zu verbessern. Die Illustrationen zu Landinos Kommentaren stammen von verschiedenen Künstlern, wobei der bekannteste unter ihnen der Maler und Illustrator Botticelli ist, der im späten 15. Jahrhundert arbeitete. Botticelli gestaltete eine Reihe von Illustrationen, die die Szenen aus der "Divina Commedia" lebendig werden lassen und mit Landinos Kommentaren harmonieren. Diese kunstvollen Darstellungen bereichern das Verständnis der komplexen Themen in Dantes Werk und haben zur visuellen und literarischen Legacy dieser Zeit beigetragen. Zusammengefasst spielt Christoforo Landino eine bedeutende Rolle in der Rezeption von Dantes "Divina Commedia" im Renaissance-Humanismus, sowohl durch seine tiefgängigen Kommentare als auch durch die Verbindung zu illustriertem Kunstwerk, das diese Hauptwerke begleitete und vertiefte.

Christoforo Landino è stato un importante umanista e commentatore fiorentino del XV secolo, noto per le sue opere sulla letteratura e sulla filosofia. Nato a Firenze nel 1735, Landino si distinse non solo per le sue riflessioni sui classici, ma anche per l'interpretazione di opere letterarie fondamentali della storia della letteratura italiana, tra cui la celebre "Divina Commedia" di Dante Alighieri. I suoi commenti alla "Divina Commedia" sono particolarmente significativi per diversi motivi. In primo luogo, offrono un'analisi approfondita della struttura e del contenuto dell'opera, proponendo chiavi di lettura che sono rimaste influenti nel panorama critico. Landino si dedicò particolarmente ad esplorare i temi etici e morali presenti nei versi di Dante, sottolineando l'importanza della giustizia e della redenzione. Nei suoi commenti, Landino ricorreva all'analisi filologica, interpretando i passaggi più complessi e fornendo spiegazioni sui termini e le allusioni storiche e mitologiche. Ad esempio, il suo approccio cercava di contestualizzare i personaggi dell'Inferno e del Paradiso, rivelando il loro significato non solo nell’ambito della narrativa dantesca ma anche in riferimento alla filosofia e alla teologia del tempo. In questo modo, riusciva a rendere l'opera di Dante accessibile a un pubblico più vasto, che altrimenti avrebbe potuto trovare difficile avvicinarsi a tali testi densamente poetici e filosofici. In aggiunta ai suoi incisivi commenti, Landino fu anche attivo nella diffusione della "Divina Commedia" attraverso illustrazioni. Giovanni Stradano, un noto artista fiammingo, contribuì con le sue opere a illustrare le edizioni dei commenti di Landino. Le illustrazioni di Stradano accompagnavano i testi, fornendo una visione visiva delle complessità poetiche di Dante e rendendo l'esperienza di lettura ancora più immersiva. Le raffigurazioni degli incontri danteschi, dei paesaggi ultraterreni e delle figure simboliche contribuiscono a dare vita e profondità all'interpretazione di Landino. In sintesi, il contributo di Christoforo Landino alla "Divina Commedia" e alla letteratura italiana in generale è inestimabile. Le sue osservazioni profonde e l'illustrazione delle sue opere hanno non solo arricchito la comprensione dell'opera dantesca, ma hanno anche ispirato generazioni di lettori e studiosi nel loro viaggio attraverso uno dei capolavori più significativi della letteratura mondiale.

Christoforo Landino, né en 1424 à Florence et mort en 1504, était un éminent poète et humaniste italien, connu pour ses travaux sur la littérature classique et son rôle dans l'essor de l'humanisme de la Renaissance. Il est surtout célèbre pour son commentaire sur "La Divine Comédie" de Dante Alighieri, une œuvre majeure de la littérature mondiale. Les commentaires de Landino sur "La Divine Comédie" sont considérés comme parmi les plus significatifs. Il a rédigé ces commentaires pour rendre le texte de Dante plus accessible et compréhensible pour un public de son temps, qui, bien que profondément immergé dans la culture classique, pouvait parfois se heurter à la complexité linguistique et philosophique de l'œuvre de Dante. Les commentaires de Landino sont remplis d'explications détaillées, d'analyses sur les allusions historiques et littéraires, ainsi que d'interprétations personnelles qui visent à éclairer le lecteur sur les thèmes profonds de l'œuvre, tels que la moralité, la justice divine et l'amour. Dans ses commentaires, Landino s'attarde également sur le langage poétique de Dante, explorant les métaphores riches et les références à la mythologie classique qui parsèment le texte. Il essaie de relier les idées de Dante à la philosophie aristotélicienne et aux concepts contemporains du bien et du mal, ce qui reflète l'esprit humaniste de son époque. L'illustration des commentaires de Landino fut une collaboration notable avec des artistes contemporains. Parmi les illustrateurs de ses commentaires, le plus célèbre est sans doute Botticelli, dont les illustrations pour "La Divine Comédie" ont aidé à donner vie aux visions spirituelles de Dante. Les dessins de Botticelli se distinguent par leur expressivité et leur capacité à transmettre les émotions intenses et les croyances mystiques qui émergent de la poétique de Dante. Ainsi, les commentaires de Christoforo Landino, enrichis par les illustrations de Botticelli, ont non seulement contribué à la compréhension de "La Divine Comédie" mais ont également influencé la manière dont cette œuvre serait perçue à travers les siècles. Ils restent une ressource précieuse pour les lecteurs et les chercheurs souhaitant naviguer dans le monde complexe et fascinant de Dante.

Die Kapelle Scrovegni in Padua - eine fiktive Diskussion zwischen Dante und Giotto

In the heart of Padua, an intimate yet profound conversation unfolds between Dante Alighieri, the renowned poet, and Giotto di Bondone, the illustrious painter. They meet under the vaulted arches of the newly constructed Cappella Scrovegni, a chapel commissioned by the wealthy banker Enrico Scrovegni. With an air of urgency and reverence, they discuss the design of the frescoes that will soon adorn the chapel's walls, each panel a testament to both divine glory and human experience. Dante, his brow furrowed in reflection, speaks first. "Giotto, the frescoes must capture not just the stories of Christ and the saints but embody a truth that speaks directly to the hearts of all who gaze upon them. The message must resonate with humility and the need for redemption. Enrico Scrovegni seeks not merely to decorate this sacred space but to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art that harmonizes all elements into a singular expression of faith." Giotto, ever the visionary, nods thoughtfully as he considers the weight of Dante’s words. "Indeed, my friend, the frescoes must transcend mere decoration. They should evoke emotion and contemplation. Each figure, each gesture, must tell a story. The colors must breathe life into the scenes of the Last Judgment and the life of the Virgin Mary. We must balance the grandeur of heaven with the stark realities of sin and redemption." As they walk through the unfinished chapel, stepping through the contemplative silence interrupted only by the distant sound of chisels and brushes, Dante gestures toward the space where the main altar will stand. "This is where the essence of the experience will dwell. From here, worshippers will seek solace and forgiveness. The frescoes must guide them, echoing the cries for mercy that Scrovegni himself surely has, given his past in usury. What better way to atone than through an art that speaks directly to God's love and justice?" Giotto sketches in the air with his fingers, imagining scenes that will flow from the corners of the chapel towards the center. "We can depict the ethereal light of paradise above and a stark representation of hell below, employing chiaroscuro to contrast the divine and the damned. The figures must be alive, capable of moving the soul. Among them, I envision Enrico himself, standing in humble supplication, flanked by the saints who can intercede on his behalf." The poet considers this, a stirring image taking shape in his mind. "It is vital we stay true to his essence, Giotto. We must convey both his wealth and his desperation. His riches may have built this chapel, but it is the weight of his conscience that drives him to seek forgiveness. Our work here must reflect the duality of his purpose: to create beauty while grappling with the ugliness of his past dealings." As they pause to look out of the chapel into the surrounding landscape, the golden light of noon bathes the countryside in warmth. Dante muses, "Imagine the people arriving here, burdened by their own sins, seeking the same solace that Enrico yearns for. They must feel that they are not alone in their struggles, that each figure painted on these walls knows their plight and extends a hand in compassion. This chapel can be a sanctuary for their souls." Giotto’s eyes light up with inspiration as he envisions how to weave the everyday into the sacred. "What if we incorporate scenes of ordinary life, alongside the biblical stories?

Fishermen, farmers, and families amidst the grandeur of heaven and the horrors of hell, all interlinked. We show that every life is significant, that everyone has the capacity for sin and redemption, and thus, the frescoes will resonate deeply with all who enter." "A noble idea indeed, Giotto!" Dante responds, his passion igniting. "Each individual’s journey reflects an aspect of the greater narrative. Just as in my writings, I strive to depict the universal in the personal, so too must your art speak to the myriad lives intertwined with Enrico's. "We must also ensure that each panel connects seamlessly, creating a narrative flow. When one walks from the entrance to the altar, they should feel as if they are embarking on a pilgrimage through the trials and tribulations of humanity towards salvation." Positioning himself amidst the sunlight filtering through the chapel, Giotto smiles, clearly enthusiastic about the venture ahead. "And let us not forget the importance of facial expressions and body language. A single tear, a furrowed brow—these small details can convey a lifetime of regret or joy. I envision the moment of Christ’s resurrection radiating hope, contrasting sharply with the despair of the damned, drawing hearts towards the grace that awaits them." Dante, already weaving words into a rhythmic cadence, begins to articulate the vision. “The frescoes will speak, Giotto. They will whisper to the souls of the viewers, urging them to reflect on their paths. Enrico’s plea for forgiveness will echo through time, reverberating in the hearts of those who come after him. In this sense, both you and I play roles of both artist and witness, capturing the essence of a moment that transcends our time.” As they finalize their ideas, a renewed sense of purpose envelops them. The frescoed walls of the Cappella Scrovegni will soon brim with vibrant imagery, alive with the struggles and triumphs of humanity. Through their combined talents, Dante and Giotto aspire to create a legacy that will breathe life into the chapel, forever reminding its visitors of the power of art and faith intertwined in a quest for redemption. The project ahead is daunting, yet the passion fuels their creative spirits, setting the stage for a masterpiece that will endure through the ages, holding the sacred space for humble prayers, heartfelt confessions, and the eternal quest for divine mercy.

Grabmal des Bankiers Enrico Scrovegnis

email: ceng1@gmx.de

© 2025. All rights reserved.

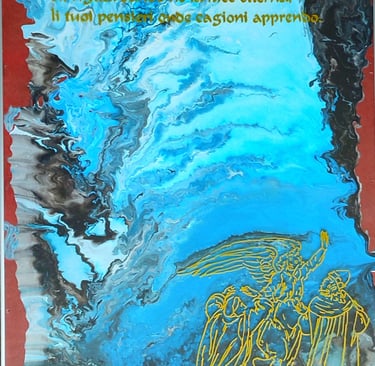

Das Ende der Reise - Aufstieg zum Empyreon

Wie, wenn ins ew'ge Licht mein Auge schaut,

mich dieses ganz mit seinem Strahl entzündet,

so ist mir deines Denkens Grund vertraut

Paradiso 11, 19